January 2022 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the Bloody Sunday massacre. On January 30th, 1972, British troops fired into an unarmed civil rights march in Derry, Northern Ireland, killing fourteen and wounding over a dozen others. This repression followed a mass movement confronting the British forced partition of Ireland and ongoing rule in the North as well as demanding equal rights, equitable housing, and an end to police brutality. In 1969, and again from 1971–72, residents established the autonomous area of Free Derry, pushing police and eventually the military out of Catholic-majority areas. Here Rampant talks with Eamonn McCann, a veteran socialist and one of the leaders of the civil rights struggle about the lessons of Free Derry and its relevance to current struggles against the police and for democracy.

brian bean: In the United States, the movement against policing has always been a detonator of larger social struggle. Can you talk about the relationship between the struggle against British imperialism in Northern Ireland and the Free Derry movement of fifty years ago? What was the relationship between the Irish civil rights struggle and the struggle against the police?

Eamonn McCann: I suppose the relationship between the civil rights struggle and the police was dictated and determined by the police themselves. At the earliest stage of the civil rights movement, from the spring of 1968 onwards, the movement was very peaceful. It was one of its principles. Anyone who stepped out of line would be chastised and warned off, because the main leadership of the movement was convinced that the way forward was to win as wide support as possible, within Northern Ireland, Ireland generally, and in England. The feeling was that any violence would discredit the movement.

Now that seems very naïve in retrospect but that is what was believed at the time. It was despite our peacefulness that we were faced with heavily armed squads of police who, within a few weeks, actually started attacking it, hampering it, and attempting to drive it off the streets. Now that was not something, it genuinely wasn’t, that was hoped for by the civil rights movement. There were a very small number of people at that time, who were saying “let’s take the cops on.”

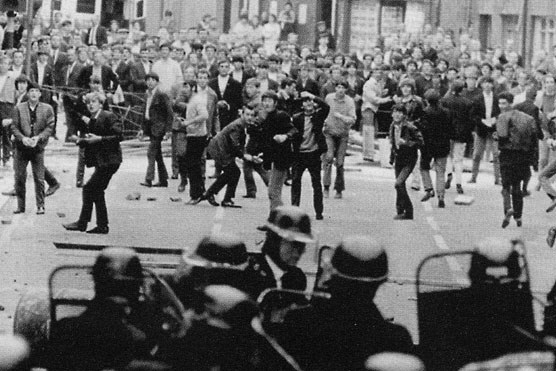

What turned the tide was the police attack, a series of attacks on the civil rights movement. The first time that that happened to some political effect was in the first week of January 1969 when we had a civil rights march from Belfast to Derry, organized and led by students from Queens University. The demands of the march were very moderate. There were some demands about policing, we wanted the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC)—the local police force—disarmed. The RUC on patrol, on traffic duty were armed, which is intimidating. We wanted the B Specials, the auxiliary police force whose membership was drawn mainly from extreme elements of the protestant unionist community, withdrawn.

The civil rights movement became very quickly entangled in the politics of Northern Ireland and in the politics of policing. The pro-British Unionist Party, from the very beginning, encouraged the police openly in public statements: “Go in, beat them off the streets. These are rowdy IRA [Irish Republican Army] people. They’ve got guns hidden under their beds. They’re gonna murder protestants,” and all the rest of it. So you had a cacophony coming from unionist politicians on the one hand, and then our experience of the police on the other. The whole thing combined in a vicious brew of disenchantments. And that really broke the relationship between the police and both the civil rights movement and the Catholic community in general.

And that was a big change.

You describe people becoming politicized in response to the repression of the police, which led into a series of protests and riots beginning from January 1969 until August. In August, the movement in Derry “won a battle,” to use the language from your book. You pushed the police back behind the barricades of the neighborhoods of Bogside, Creggan, and some of the other Catholic neighborhoods in Derry and made them police-free zones. That then was the first experiment of Free Derry that lasted until October. One of the demands that was issued by the Derry Citizens Defense Association (DCDA), of which you were a part, was for the disarming of the police. Can you talk about how that battle of the first Free Derry was won, and why the demand of disarming the police was one of the central demands?

Well it’s important to say that very few things during the civil rights movement were planned.

There were times when things worked and we sort of pretended, even to ourselves, that we’d planned it. An awful lot of it was spontaneous. You had mainly young people on the streets, standing with stones, fighting against the police. I would’ve been seen by some people as a leader. But believe you me, nobody was following me, you know? Some of us imagined that we were leading. Calling for resistance to the police right from the beginning was like calling for the sun to rise tomorrow with a view of taking responsibility for its eventual appearance on the horizon. This happens—in my experience—in radical movements all the time.

But the police attacks on the civil rights movement were absolutely crucial to that period. The first time a police baton cracked down on the skull of a civil rights marcher, the terms of engagement had begun to change. As did the arguments about the politics of policing and what our attitude ought to be. When the cops started attacking us on a regular basis, arguments about how to deal with the police quickly became abstract, became academic. In the first iteration of Free Derry, when barricades were thrown up around the area it was simple. The cops were coming in and attacking the area or chasing civil rights demonstrators back into our area.

The first little barricades that went up against the RUC were only three, four feet high. They were just piles of rubble. They weren’t serious. They weren’t going to stop anybody. They were more marking our territory than a serious attempt, actually, to prevent the police getting in. But of course that escalated, not just physically, but it escalated in people’s minds as time went on. We became involved in something more profound here than just keeping the police out. That was the main factor in the development of how the movement politicized.

We were very much reacting to what the cops and the state were doing. What added to this politicization was the fact that there were leading unionist politicians in Northern Ireland saying to the police, “You’re not going in hard enough. Hit them harder.”

Looking back on it, I would say now that we ought to have been more coherent politically. We ought to have taken a calmer, cooler response. We ought to have taken time to sit down and analyze what was happening around us. But you know, when you’re a certain age, action is very exciting. If someone were to say, “Let’s have a meeting and discuss it,” you say, “Fuck off.” We’re not going to go into a room and discuss it while the cops are down right there. It was exhilarating at the time. It was also silly. Where there were mistakes to be made, we made them.

Of course that escalated, not just physically, but it escalated in people’s minds as time went on. We became involved in something more profound here than just keeping the police out.

And when we look back on it and try to draw lessons from it, we have to begin by acknowledging that we didn’t really win, did we, at the end of the day? So why didn’t we win? Why didn’t the people with our radical socialist ideas who sparked the original civil rights movement stay at the fore of things? Was it our fault? Was it other people’s fault? Was it just history weighing down on us? Probably it was all of those things, but another factor was, as someone (it might even have been Lenin) said: An ounce of action is worth a ton of theory. That is true. But it’s also true that without theory, no action can be coherent politically. We made lots of mistakes trying to balance that.

There were parallels with what was happening elsewhere, as in Paris in May 1968. This was a pattern. We made connections with what was going on in France, in the US, in Prague, with Rudi Dutschke, Daniel Cohn-Bendit, the people involved in Chicago, and so on. They all shared, as we did, this opposition to authority, and they came under attack. They run at the authority with a waltz, with a jauntiness. Mary Hopkin sang: “Those were the days, my friend. You know, we thought they’d never end. We were young and sure we’d have our way.” That pinned it, that was the expression of what was going on.

During the first Free Derry, you found that you had created this liberated territory that was a no-go-zone for the police. In your book you described a host of day-to-day problems that had to be dealt with. You wrote how an alternative “police force” was created to deal with petty crime. Could you talk about these day-to-day problems, how they were managed, and especially about this “force”? For example, you mention how often a stern lecture on solidarity was the simple substitute for punishment. What sort of experiments were going on in those two short months?

You have to keep in mind that, yes, it was an experiment and it wasn’t an experiment set up deliberately to prove something. It was a spontaneous experiment. We were making it up as we went along. We weren’t admitting that at the time because we had to appear confident. You had to appear as if you knew what you were doing even when you didn’t know what you were doing.

At the beginning of the civil rights movement we had this phenomena of civil rights stewards. They were who stewarded the marches. In theory, the stewards were out to protect the marchers, but there was also an element of control involved in it as well. They were a moderate element, so to speak. They would say, “We got to have peace, we can’t have hooligans, we can’t have people who are undisciplined creating problems.” So there was control involved in the civil rights marches in the first place. And when it became semi-spontaneously Free Derry, the task of the civil rights stewards became that of controlling the area.

Now when I say control, I don’t mean that people were being threatened; but there was this section of people who saw it as their purpose to make sure that Free Derry was a well-ordered occupation. We couldn’t just have people smashing windows or fighting with one another. And the civil rights march stewards became sort of a “police force,” although it was some time before anybody called them that, and, then, they called them the Free Derry Police in a jocular way. Within that group of people, the more self-confident people came to the fore, the better organizers, people who were recognized in the area as having fulfilled a serious function prior to these events, and so on. So we got very quickly a layer of people who were genuine products of the struggle and who also saw themselves as maintaining good order within the struggle so it didn’t just scatter.

The thing that I remember most is that the slogan was not “Smash the State.” It was: “What the fuck are we going to do now?” There was a degree of chaos around the whole thing. It was undisciplined. And if it had been too disciplined, it couldn’t have worked.

There was a degree of chaos around the whole thing. It was undisciplined. And if it had been too disciplined, it couldn’t have worked.

If you’re inviting young people to come out and throw stones and petrol bombs at the police, it’s very difficult then to tell them, “But behave yourself on other occasions.” You can’t do that. You can’t go around saying, “Wait a minute, we’re organized here. I’m a leader and that one’s a leader and she’s a leader,” and so on. It was very messy, but small wonder.

How were things like petty crime handled by these stewards who were attempting to keep a degree of order and organization in a chaotic situation?

Well, during the period of Free Derry, there was very little petty crime. It plummeted. I recall journalists from outside would come in, and they would think that there must be anarchy–and they didn’t mean that in a good way. They thought people must be living in fear. And then they discovered the people were very happy and content most of the time. There was a sense that solidarity meant that you didn’t smash other peoples’ windows. You didn’t harass them in the street. You didn’t steal from them. I don’t want to exaggerate this, but in a sense people thought they’d be letting the side down if they behaved in ways that they behaved when the RUC was in control. That, I think, is the main reason why crime fell.

Honestly, I think it did not have a great deal to do with the Free Derry Police. Some people exaggerated that we had this police force that maintained peace through persuasion. It just happened. The lack of crime in the Bogside was something we thought about afterward, but I can’t remember thinking much about it at the time. It just took place, it was just a natural development. Just think about it, if you’re all together and there’s need for vigilance and to be organized, and you need to mind the barricades at night and so forth, then having a fistfight with your friends over a football match or something doesn’t make sense.

The young people at the Bogside wouldn’t have stood for any heavy-handed policing. They’d have said, “Fuck off!” if anybody had come along and ordered them about. Some accounts I’ve read, and probably some of the accounts I’ve written, retrospectively impose order on chaotic events in order to understand them and convey them to other people.

There was a contradiction written into the Free Derry Police. How can you have a “free police”? That’s a factor that perhaps hasn’t been analyzed enough.

In October the barricades came down, and just about a year later, in August of 1971, the second Free Derry rose up with massive resistance to attempts by the British to carry out internment: mass arrests, raids, prolonged imprisonment. Can you talk about what sort of obstructive behavior and struggles created the second Free Derry? The second no-go-zone this time held off not just the RUC but also the army.

Indeed. And the second one was more serious or substantial. It lasted longer, and it wasn’t as spontaneous, though of course there were spontaneous aspects to it. It began for very practical reasons. In the early hours of August 9th, 1971, British soldiers came not just into Bogside, but into Catholic working-class areas all across Northern Ireland, smashed their way into houses and arrested 341 people. About 30 of them were from our area. I knew many of these people. They were arrested and taken off under the Special Powers Act, with no charge, no trial, no proceedings of any kind; they just threw you into a prison cell.That caused widespread anger.

Now, there had been internments in Northern Ireland before, during World War II. And internment had been used between 1957 and 1962 when there was a spluttering and unimportant IRA campaign.1Known as Operation Harvest. The community was not unused to internment. But this was different. It was on a larger scale. It was done by the British army and not by the local police force. And people had, over the preceding couple of years, developed self-confidence out of confronting authority. They simply weren’t going to stand for it.

I was in London when the interments happened and I immediately got on a plane at seven in the morning. At lunchtime, I arrived in the Bogside to find meetings going on everywhere. Loads of people around, very angry. The sentiment was, “We’re not going to let them do this again. Darkness is gonna fall tonight, and if we don’t do something, they’re gonna come back in. What are we gonna do?” That’s where Free Derry came from. It had a practical purpose–you put up barricades to stop the cops and the British soldiers from interning people without trial.

That’s where Free Derry came from. It had a practical purpose–you put up barricades to stop the cops and the British soldiers from interning people without trial.

That incited much wider support. While a year before there were lots of people who didn’t want to be strutting around and driving the cops out, the idea that we won’t let them take our people without charge or trial, that we won’t let them smash their way into our houses without any response at all, moved people to take action.

Even very moderate people came out. I remember my surprise the next day when school teachers and shopkeepers came out. There were a lot more adults, working people, and more women out on the barricades. It changed the character. So the second Free Derry was politically a more serious matter than it had been in its first, rather joyous, iteration.

How did you maintain self-management and alternatives to policing organized for a year? In the context of the militias of the two Irish Republican Armies being more dominant politically, how was it that the Free Derry Police were independent of both the Officials and the Provisionals?

One of the big differences between the first iteration of Free Derry and the development of the second Free Derry is that the struggle had intensified. It was no longer petrol bombs and stones; there were now arms involved. Not only were there guns, but there were the two IRAs actively operating in the area, and that of course changed the calculus with regard to what you could and what you should do in terms of keeping the cops out.

I believed at the time, and still believe, that secret armies don’t help develop mass consciousness. People were frightened of armed men. Of course they were. While they might be people that they knew or from the area, having guys with AK-47s strutting around the place saying we are the security, that will change things. That meant that while we still had something that saw itself as the Free Derry police force, when there were armed groups also around the same area it made less sense, and it was obvious that Free Derry Police don’t have any decisive power or control.

Like everything else from the start of the Northern Ireland Troubles, the Free Derry police force was chaotic. We had people who just went to this little West End hall in the middle of the Bogside, and somebody established that as the “police headquarters.” Who did this? I don’t know. But then suddenly there were thirty or forty guys who are part of this unit based around the bottom of Westland Street.

What did they do?

I used to ask them that: “What the fuck are you guys doing?” I remember I said that once to Bobby Toland, who emerged as the “chief of police” in Bogside. How this happened, nobody knows. One of his tasks was, for example, to equitably distribute cigarettes to the vigilantes on the barricades. They would handle other little things like disputes about this or that and all sorts of opportunism and so on.

Then there was Tony O’Doherty who was an international footballer from Northern Ireland from Creggan. He seemed the most obvious person to put in charge of the Creggan estates. He was respected. He was that kind of guy. You don’t expect to have an international footballer patrolling the streets with an armband before going back and setting up the pitch to play another game. But the whole thing gave a role to people who were not willing, didn’t politically approve of, or were not able to take part in any armed struggle. There were quite a number of us who had been vigorously active in the civil rights movement, who had that spirit of the 1968 events around the world, and perhaps naively wanted to see that movement progress and swamp the state in sheer numbers.

There was quite some tension in the Bogside at that time between the advocates of armed struggle on the one hand and a lot of the rest of us on the other. And when I look back on it now, I see the rise of the IRA as the decline of the civil rights movement. You couldn’t compete with it. And of course the leaderships of the IRAs took advantage of that. It’s sometimes written that the emergence of the IRA as a serious force in Northern Ireland started with a reflection of people deciding or being forced into supporting armed action. It wasn’t really like that. It’s that when the armed actors go into operation, then it’s very difficult for anybody else in the vicinity to act.

When the armed actors go into operation, then it’s very difficult for anybody else in the vicinity to act.

Of course the IRA and the forces of the state were not doing the same thing, but there were strange parallels. I can remember on Rossville Street a shout suddenly going up: “Clear the street. Clear the street,” and that was to allow the IRA to take a few potshots without putting the crowd in danger. The other people who would be shouting “clear the streets” were the British army. It was a very curious experience.

I know what happened, and I know why people were doing it. But I still don’t know how to figure out what was the proper and appropriate attitude to take. It just happened. And I think we failed. It was a failure of leadership because there was a lack of clarity. For a couple of years we were sort of surfing along exciting events, but then, when it comes down, when the shooting war starts, all that heavy enthusiasm disappears. That’s how I think about it now.

One of the things that closed the period of the Free Derry experiments was the events of the Bloody Sunday massacre, which of course you’ve written extensively about. The fiftieth anniversary just passed, and justice still has not been achieved. Could you talk a little bit about Bloody Sunday and about it as a reaction to the challenges posed by the iterations of Free Derry?

By the time of January 1972, Free Derry was very established. It was there and had been for months and people got used to it. The postal service was operating, milk was being delivered, shops were open, and so forth. This must have been even more ominous to the authorities than people throwing stones at them. When you read memoranda of the operational office of the British army at the time it quickly becomes clear that the top leadership of the British army in Northern Ireland and the guys over in London who were in overall control were more frightened of Free Derry than they were of the IRA.

“Fleet of foot and full of guile, the Bogside hooligan is a formidable enemy.”

Their exchanges are full of descriptions of what humiliation it was that you had this bunch of no-goods, working class louts, preventing the British army from getting into a part of what constitutionally was Britain. They were enraged by that. For example, there were a number of memoranda from Major General Robert Ford, who was the commander of land forces in the North. He came to Derry a couple of times in December 1971 and the first week of January 1972 and wrote up his opinions. And it scarcely mentions the IRA. Now of course the IRA was on their minds as well; but it was all about the hooligans. There’s a wonderful memo from one of the British army commanders of a garrison regiment in Derry. He began with a wonderful sentence: “Fleet of foot and full of guile, the Bogside hooligan is a formidable enemy.”

It sounds like a beautiful poem.

It is. Julius Caesar wrote like that about Gaul. When Julius Caesar was passing through Gaul and dealing with all these “savages,” he was fascinated by them. I think there was an element of that in the upper echelons of the British army, in the way they perceived and felt about the hooligans of the Bogside.

So that certainly was one of the reasons that they wanted Free Derry smashed. They could fight in the countryside and elsewhere, they could have shootouts with the IRA and be confident that they could probably win in the long term. But this was a more fundamental threat to all established ideas of how society should be run.

The British army theorists and strategists were ahead of us. The shooting and guns were much more exciting on the face of it, but actually, it was the mass mobilization that had carried us that far forward since the beginning of the civil rights movement. We sort of lost sight of that a wee bit. The hooligans were insufficiently politicized, and the people who purported to be political leaders at the time have to take some responsibility for that.

So the more fundamental challenge of Free Derry that threatened the British was that it was being self-managed and organized outside of the auspices of the British state: the mail was being delivered, there were no police, and they couldn’t get in?

Yeah, it was. When I look back on it now, it seems more remarkable than it seemed at the time. The idea of operating without any police force came naturally to people. It came as an act of defiance, but it was an act of defiance that didn’t require anything of you other than you maintaining your defiance. And putting the barricades up was obviously a real symbol of that.

But again, there were also, within the Bogside, people who were saying, “This is very destructive, and the election is going to come around, and we’ll lose the support. The bishop says he’ll support us if we all get back and take the barricades down.” I remember this little delegation coming back from the bishop and some of us thinking, and saying, what the fuck does this have to do with the fucking bishop?

The idea of operating without any police force came naturally to people.

There was always a moderate element, who tended to be in the professions or headed for them, good moderate, peace-loving Catholic people who didn’t want any of these disruptions. They would say, “Look, if we can get a deal here we can stop all this nonsense.” One of the big arguments used against us was jobs. They would say: “Who’s going to invest in this area if all this violence is going on?” That was a constant thing. We had high unemployment. Before Free Derry we had run an unemployment action committee. And I can remember being shouted at. They said, “You were a campaigner for jobs. Now look at you. You’re destroying jobs. You’re destroying your own town.”

It would be wrong to say that there was unanimous support within the community for what was happening. There was not unanimous support at any time. When we look back on it now you sometimes have some local historian presenting a sepia-tinged image of the proletariat on the march. Actually it was a lot more complicated than that. All history is.

Before, you alluded to assessing what happened after these events, and so I wonder if you could talk a little bit how you assess things in the post-Good Friday Agreement context. What do you see as the current struggle? Specifically, I hope that you can talk a little about colonialism in the Irish context.

Ireland was a colony for a few hundred years. There’s an old nationalist MP at Westminster who once remarked that Irish oppression started when Strongbow landed—the Earl of Pembroke, who landed in 1170—and it won’t be over until Cromwell is let out of hell. That’s a long struggle, and I often share in the strain of thinking that our main difficulty here is the bloody Brits oppressing us, though I know intellectually and politically that is not the whole story. But there is a long tradition of that strain of thinking in Ireland, of seeing the struggle as an anticolonial struggle similar to the model of other anticolonial struggles. Now that was perfectly, absolutely true of Ireland at the beginning of the twentieth century.

I believed in the 1970s—and I now believe even more strongly—that that wasn’t an appropriate model or guide for action. Republicans who had fought in 1916, 1920, 1921, 1922, and so forth were now in power in the south of Ireland. They were the government. They were also using internment without trial against people. They were oppressing women in a way that women were not oppressed in Northern Ireland. They were on the right wing in economic policy and all the rest of it. So to say we have to follow the traditional Republican line, when that’s the way it had ended over most of the territory of Ireland—there is, at the very least, an occasion for argument, for debate, for disputation. But if you started arguments about these things, somebody would say you’re a traitor, that you’re dishonoring the ancient Irish tradition of armed resistance to the British. I’ve got no moral objection to armed resistance to the British in Ireland or anywhere else, but it is not a political philosophy in and of itself.

In Ireland, the distinction between nationalism—even at its most militant—and socialism is that the nationalist seeks to represent “the nation,” and all classes within it are all one as Irish people. For them, to introduce any other contradiction is seen as disrupting the nationalist narrative—and it is disruptive. You sometimes have to fight very hard to say that the fact that I don’t support the Provisional IRA’s campaign does not mean that I am against liberation and the recognition of discrimination and racism. I just think there’s a better way to fight it.

These are arguments that still go on today, and not just in Ireland, of course. I think this argument is echoed around the world, everywhere people rise up against colonial or imperialist power. Should we seek to recruit and cohere everybody here who’s against the British. Or should we work out what section of the population, what class, is actually objectively able to overthrow imperialism and not just to change the regime but to to change everything?

There is a very strong echo of that still going on in relation to Bloody Sunday. The argument is about whether you should seek to win the support of the most powerful people in the world, or whether you should look to the powerless mass of people around you. That isn’t an abstract or a sentimental debate, but a real debate.

We campaigned for years for the truth about Bloody Sunday. And then, in 1998, along comes Prime Minister Tony Blair who announces that there’s going to be a new inquiry under Lord Saville. Saville works for all these years, produces a report, and the report says that everybody killed and wounded in Northern Ireland on Bloody Sunday were innocent, and that the army’s actions were “unjustifiable.”

Now, obviously a large majority of the people who had marched for the truth about Bloody Sunday said: “Okay, we’ll accept that. That’s as good as it’s going to get.” They would say: “So, because our people have been declared innocent and a handful of paras have been made available for prosecution, that is sufficient unto the day.”2“Paras” are paratroopers of the British army who took part in the massacre. I remember one senior Irish Republican saying on the day we had the Saville report in our hands, “It’s not going to get any better than this, so no need to march any more. We solved this. I’ll put that in the past.”

The argument is about whether you should seek to win the support of the most powerful people in the world, or whether you should look to the powerless mass of people around you.

Had it not been for “extremists” who said, “No, we are going to fight on. We’re going to march on, even if our marches initially are a tenth the size of the marches that preceded Saville,” we wouldn’t have the situation today where there is much wider understanding that it’s not just individual soldiers, it’s not just because they’re crazy paras, and they’re brutal and all. They are all those things, but there’s something else behind them. We’ve got to take on the government. They’re responsible. Denounce them. Point the finger of blame not at Soldier H, who at the time was a twenty-four-year-old member of the paratrooper regiment from the north of England. Politically, he’s a moron; he didn’t create this. They just sent him into Bogside to do what the establishment expected paratroopers to do.

I can name the British army officers and ministers at the time who were involved: the prime minister Edward Heath, home secretary Reginald Maudling, Lord Carrington, who was the minister of defense, Sir Harry Dalzell-Payne, Lord Balneil—they did it. They did it. They presided over all this. They’re off the hook. They and their descendants welcomed the Saville inquiry saying, “Oh, you know, a lot of blame to go around. We didn’t behave very well. We’re very sorry for what happened. So let’s all shake hands and call it quits.” And an awful lot of people in Ireland, North and South, particularly people in positions of power, accepted that.

The brutes at the bottom must not be made to bear all the blame for crimes contrived by the crooks at the top.

But not everybody has accepted it. We had a march of 10,000 people who didn’t accept it on the fiftieth anniversary a couple of weeks back. It was as big as anything that had gone before. There are very few things in my political history that I can look back on and say, “Yeah, I did the right thing there, and it had an effect.” But the fact that I took that line about the Saville inquiry I think made an impact. It was better. We were getting at the real culprits. The brutes at the bottom must not be made to bear all the blame for crimes contrived by the crooks at the top.

Don’t let the ruling class off the hook. And you know, they’re let off the hook fucking everywhere. Everywhere. “We’re terribly sorry, it was that guy, he did that without orders, he was crazy, he was an extremist anyway.” They said that in India. Lord Mountbatten made this statement in 1947 when the British left India about how they regretted the terrible things that had been done. Never an admission. You did those terrible things. Fucking British royal family. Senior members of it were involved in the oppression in India, Northern Ireland, and elsewhere.

I feel like there’s two really important lessons threaded through your comments. The first is never let the ruling class off the hook, and the second is watch out for the people who say, “Stop. This is the best we can get right now.”

Yeah, the people who say that have always been saying that. They’ve been saying “stop” since before we started! Always at every juncture there are people who say, “All very well, but look at these terrible things that are happening now. We never should have approved murder and torture”—which we didn’t! But that doesn’t mean you just go down on your knee and accept what’s offered to you at any particular time. There’s an awful lot of that. And then of course there’s also a great many people in Ireland, North and South, who have built political careers on the bones of honest fighters against imperialism, and they’re still doing it. They’re still doing it.